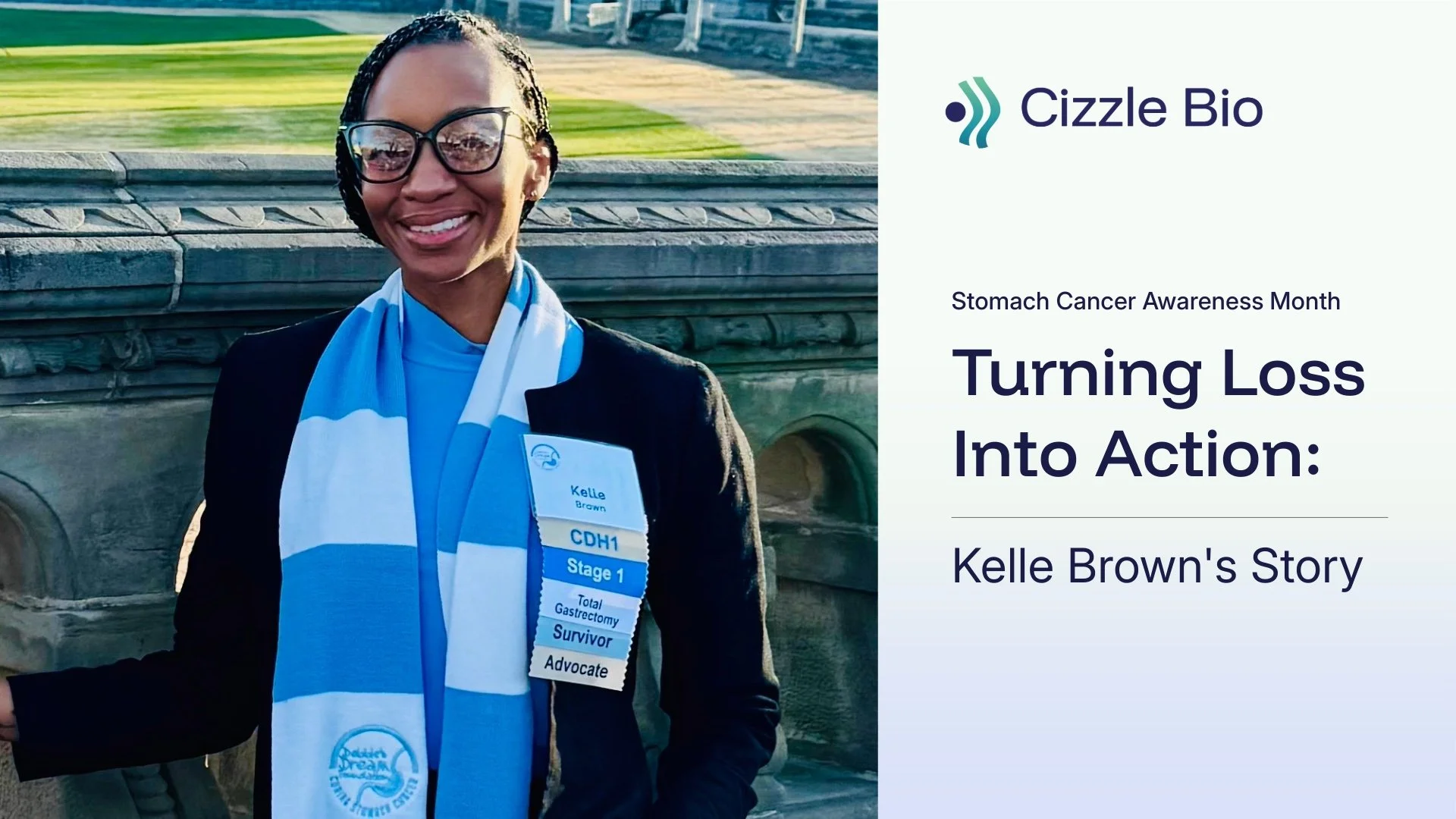

Turning Loss into Action in the Fight Against Stomach Cancer

Kelle Brown knows how quickly stomach cancer can steal a life. It took her sister, Karmen, in just 52 days. When Kelle later learned she carried the same genetic mutation, she turned her fear into action. The surgery to remove her stomach not only saved her life, but it also gave her a new purpose—to make sure others are diagnosed earlier and heard sooner.

In 2016, Karmen Brown was young, healthy, and full of energy. She worked, exercised, and lived an active, vibrant life. But when persistent stomach pain, rapid weight loss, and exhaustion began to take hold, doctors repeatedly sent her home with reassurance instead of answers. It wasn’t until one physician decided to keep her for observation that the truth emerged. Tests revealed cancerous cells, and results sent to the Mayo Clinic confirmed Stage 4 diffuse gastric cancer (DGC). Karmen never left the hospital again. She was 35 years old.

Two days before Karmen passed, her care team suggested the family be tested for a rare genetic mutation called CDH1 linked to hereditary diffuse gastric cancer (stomach cancer) and lobular breast cancer. Their suggestion proved life changing. Kelle, a U.S. Army respiratory therapist who had served since 2007, requested genetic testing through her military healthcare providers. Her request was denied four times, but finally, persistence paid off. The day after her birthday, the results came—positive for CDH1.

The call forced a decision that few people ever face. Either remove her stomach before cancer could develop or risk the same outcome as her sister. “I didn’t know anyone who had ever had their stomach removed,” Kelle recalls. “I didn’t know what kind of life I could live after that.” Uncertain about the right path, she chose to wait and undergo close medical surveillance. But when her endoscopies began showing worrisome changes and eating became difficult, doctors urged her to act.

Kelle turned to MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston for treatment, and her surgeon performed a total gastrectomy, or stomach removal, in January 2018. Pathology confirmed what she had feared—four small tumors, Stage 1b, were already forming. “My surgeon told me that if I had waited much longer, I probably wouldn’t have made it to April,” she recalls. The surgery saved her life, but it also redefined her purpose.

Just 11 months later, genetic screening revealed she was also at risk for lobular breast cancer. A mammogram revealed a mass in her left breast and micro calcifications in her right breast. After a biopsy, early-stage cancer was found, and Kelle opted for a double mastectomy—another act of courage rooted in prevention. Through both surgeries, Kelle remained on active duty, returning to work just eight weeks after her gastrectomy. “I went right back to night shifts,” she laughs. “It wasn’t easy, but I was determined.”

That determination soon became advocacy. Kelle joined Debbie’s Dream Foundation, an international organization dedicated to stomach cancer awareness, research, and patient support. She became a mentor for newly diagnosed patients, especially those navigating military health systems or the same hereditary risks. “When people reach out—on Facebook, Instagram, wherever—I answer,” she says. “Sometimes they just need someone who has been there to say, ‘You can live a normal life.’”

For Kelle, survivorship is not just about recovery, it’s about responsibility. She speaks annually on Capitol Hill as part of Debbie’s Dream Foundation Advocacy Day, helping secure federal research funding and educating lawmakers about the urgency of gastric cancer. “When I started, there were maybe 100 of us on Capitol Hill,” she says. “This year, there were more than 200, including children who have lost parents to stomach cancer. Seeing them speak to members of Congress gives me hope that this fight will continue long after us.”

That hope extends to medical innovation. Kelle believes early detection is the key to changing the story for patients like her sister. “Early detection could mean keeping your stomach,” she says. “It could mean fewer surgeries, fewer hospitalizations, fewer people dying before they even know what’s wrong.” New advances, such as Cizzle Bio’s DEX-G2 biomarker blood test for early detection of gastric cancer, give her hope. The test, designed to detect molecular signals of gastric cancer early—sometimes before symptoms appear—could help shape a future where fewer families experience the heartbreak hers did. “If there had been an early detection test when Karmen was sick,” Kelle reflects, “maybe she’d still be here.”

She also urges clinicians to listen more closely to patients. “I’ve had doctors tell me it was impossible to live without a stomach,” she says. “Patients shouldn’t have to educate their care teams, but often we do. When we say something isn’t right, believe us.” Now stationed at Fort Sam Houston in San Antonio, Kelle balances her military career with advocacy and mentorship. Her message to newly diagnosed patients is both realistic and reassuring. “It’s going to be hard at first, but it gets better. Keep a good mindset. Ask questions. Lean on people who understand. You can live, and you can help someone else live.”

Kelle also carries her sister’s memory into everything she does. “Karmen was fearless,” Kelle says. “She’d travel the world on a whim—just because she wanted to feel the sun somewhere new. I try to live that way now. Life is too short to waste on things that don’t matter.” For Kelle, survivorship means living fully and making sure that others have the chance to do the same. It means using her story to push for earlier detection, greater awareness, and a healthcare system that listens. And it means keeping her promise—to Karmen, to herself, and to the next patient who is still waiting for answers.

This Stomach Cancer Awareness Month, Cizzle Bio honors survivors like Kelle Brown—turning loss into action, courage into advocacy, and hope into earlier detection for all.

Click here learn more about Cizzle Bio’s DEX-G2 biomarker blood test for early detection of stomach cancer.